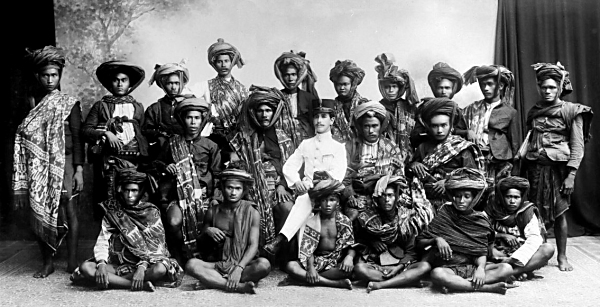

A group of East-Sumbanese village leaders proudly attired in their hinggi, posing with Dutch colonial officer in the early 1900s. Composite created by Peter ten Hoopen by seamlessly joining two images by unknown photographer, both in Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT) that were made available under the Creative Commons Licence. Please note that this photocomposition, which took many hours of work, under international copyright law constitutes a 'new work' and may not simply be copied into a publication, as Alexander Goetz did in his limited edition, clients-only booklet Voices of Sumba. This note should not be necessary as the footer of this page clearly states that all parts of the content are copyrighted, but apparenly for some people this is not enough. Sumba ikat textiles - the worst and the bestNo type of Indonesian ikat enjoys more popularity abroad than the Sumba hinggi, the large cloths of Sumbanese men, that are always created in pairs: the hinggi duku, which is worn on the shoulders, and the hinggi kalambung, worn on the hips, which is also used as a shroud. They are boldly graphic, rich in anthropomorphic figures and recognizable animal motifs, and the best of them are true masterpieces of dyeing and weaving. As is true of all ikat cloths from Indonesia, their imagery is informed by the belief system of the islanders and their adat, the narrowly prescribed set of customs and taboos. For instance: hinggi that are intended to accompany the owner must be made with vegetable dyes only. Sumba ikat textiles are full of imagery taken from the island's belief system, the Marapu ancestor cult, from their natural surroundings and daily life, often presented in the raw. As the renowned collectors Robert Holmgren and Anita Spertus note in their Early Indonesian Textiles, "many of its most memorable images are neither genteel nor delicate, but proud, proclamatory, raw, often sexually candid, or violent." Naked ancestor figures with exposed genitals stare us in the face, often with what seems like a menacing look; skull trees uncomfortably remind us of a headhunting past that, while dead in practice for almost a century, is still alive as an aspect of the culture that fill the Sumbanese with pride. Openness to foreign influences

On East Sumba, ikat cloths of more than two colours used to be made exclusively for the maramba, the aristocracy (commoners being limited to indigo on white only), and for this prestige seeking class, any association with power and regalia was welcome. A common motif from the early 20th C. for instance were busts of Dutch Queen Wilhelmina (Cf. our cloth 072), who at the time, in what was then the Dutch East Indies, represented the ultimate worldly power; mounting lions, as seen on Dutch coins (Cf. our cloth 019); coats of armour, and other elements of Dutch heraldry. Another fairly common motif in Sumba cloths, is the fire-spitting dragon known from Chinese porcelain (Cf. our cloth 017), traditionally a symbol of the power of rejuvenation, but to the Sumbanese no doubt - on account of its fearsome aspect - a symbol of power per se. All of such visual elements were incorporated in the local style and often restyled or innovated upon, gradually becoming a part of the local repertoire, and no longer seen as foreign, but as an inherent part of Sumbanese culture. Commercial senseAnother reason for Sumbanese weavers'

In the 1960s and 1970s, as the tourist business started booming, especially in Bali, the main market for Sumbanese ikat textiles, they began experimenting with more visually striking imagery, often loaned from other islands. As Jill Forshee writes in her contribution to Decorative Arts of Sumba, "many Eastern Sumbanes are well aware of the value foreigners place on 'primitivism' in their quests for non-Western arts. People [i.e. Sumbanese weavers] knowingly play on such romantic views, and the skull tree with its associations for foreigners of primitive ferocity is currently one of the most popular motifs in textiles created for a tourist market." To this end, the Sumbanese borrowed Iban Dayak patterns from Borneo that were similar to their own original headhunting motifs, but more arresting than their own traditional skull tree, andung, motifs. One could argue, as trader Jack Bavelaar did in a private exchange, that actually they were making falsifications. With some exceptions, the weaving quality in those days used to still be good to very good. Now, half a century later, most Sumbanese weavers will weave pretty much what they feel the market asks for, and if that means weaving surfers, angels, or Hells Angels into their cloths, so be it. Having said that, we have done enough to denigrate the Sumba artisans, because while many weavers, no doubt driven by sheer poverty, have sunk to produce outright rubbish for the indiscriminate tourist market - which, as they soon discovered, readily absorbs the most shoddy quality - some have retained or even developed their skills, and are true masters of their art form. A good Sumba ikat, even a modern one, is an excellent piece of work, a feast for the eyes that will produce lasting pleasure for its owner.  A Sumba weaver in Praliu Kambera, East Sumba, producing a cloth for the Balinese and local tourist markets. Note the shrill chemical colours. Unfortunately a common sight. Photo Peter ten Hoopen, 1984.

A Sumba weaver in Praliu Kambera, East Sumba, producing a cloth for the Balinese and local tourist markets. Note the shrill chemical colours. Unfortunately a common sight. Photo Peter ten Hoopen, 1984.

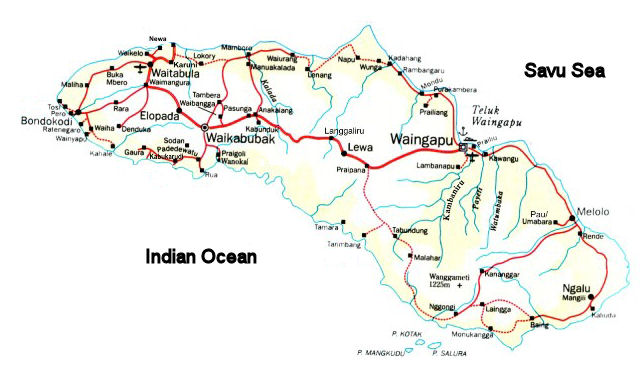

Traditional Sumba ikat weavingThere are two areas on Sumba where ikat weaving is practiced - and was practiced already when Europeans first set foot on the island: the Kodi region in the west, and eastern Sumba. The former has drawn much less interest than the latter, as the geometric Kodi cloths, while very beautiful to the eye of the expert, to the untrained eye are less immediately appealing. So usually when people are talking about a Sumba ikat, they will be referring to one from eastern Sumba. Here weaving used to be practiced exclusively in the coastal zone, the only area where local adat permitted weaving.As Brigitte Khan Majlis, curator of the textile collection at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne, one of the most quoted experts on Indonesian ikat textiles, tells us in her Woven Messages, the design, tying of the warp, and dyeing used to be the exclusive domain of women of the aristocracy, whereas the actual weaving was executed by slaves. Production was high, as ikat cloths were required for all major ceremonies, including weddings and burials. For the burial of a nobleman scores of cloths might be required, or even a full hundred - most to go down into the earth along with the deceased, a practice that brings shudders of horror to collectors and curators. The Sumbanese used and use ikat textiles both for male and female attire. The men wear large cloths, called hinggi, on average some 125 x 250 cm and always made in identical pairs, that may be used as either shoulder cloth or waist cloth, as well as turbans and belts. The overall layout of many, though certainly not all, of the late 19th to early 20th C. hinggi have eleven wider and narrower ikated bands. More recent hinggi tend to have fewer distinct areas. The women wear sarongs, called lau, that usually have additional ornamentation produced by beadwork, appliqué of shells, or supplementary warp. While such highly decorative cloths were made exclusively for the aristocracy, at major festivals some might be given to slaves as presents - not be worn however, just as keepsakes and eventually heirlooms, pusaka. Because of the high demand from the Netherlands, in the second quarter of the 20th C. ikat production centres sprang up in ports all along the northeastern seaboard. Here, the design was no longer supervised by women of the aristocracy,

Two contrasting developmentsIn modern Sumba ikat production, Khan Majlis notes two contrasting developments. One is a trend towards bolder, simpler ornaments, which require less binding. The second is a kind of revival: a trend towards textiles, particularly hinggi, which live up to the criteria found in older textiles. Aspects of this latter trend include colouration in off-white or écru (the natural colour of cotton), morinda red (which may range from brick red to a warm pink), dark indigo and bright blue (produced by short immersion in indigo), brownish black (achieved by overdyeing of morinda with indigo), and yellow accents. The revival may well be the strongest in Kanatang, with its well established reputation as the source of superior cloths.These accents may actually be ikated in, in which case we speak of lima varna (five colour) cloths, which are both rare and considered a mark of nobility, or they are simply dabbed in on the finished cloth. It takes a trained eye to notice the difference, but anyone who understands the ikat process will notice the difference immediately. In a colour segment that was applied by means of the ikat process, the pigment will bleed a little out of the bindings, but obviously can do so only lengthwise in the selected warp threads - the adjacent threads will remain unaffected. On the other hand, if the colour was dabbed in, we will also observe lateral bleeding into adjacent warp threads, a tell-tale sign of inferior production. Totemic animals and their meaningWhen studying, even cursorily, the ikat textiles of Sumba, it helps to have some idea of the symbolic meaning of certain patterns beyond the ancestor figures and power symbols discussed above. Animals play a vital part in the Sumbanese belief system, the Marapu faith, essentially an ancestor cult. (The word marapu means 'ancestor'.) Several Sumbanese clans believe that they are descended from crocodiles or similar creatures. As a result of this belief crocodiles, buaya or wuya, are highly revered and must not be killed, leave alone eaten. They also believe that crocodiles will not eat them, unless they have offended a member of the clan descended from the marapu embodied in the animal. The Sumbanese further believe that a person can acquire the special powers of certain animals by wearing cloths on which they are depicted. This totemic protection is eagerly sought, especially in times of distress or illness.Wholly apart from any supposed supernatural powers, nearly all animals common in Sumbanese iconography are representative of social status and wealth. Buffaloes and cows are often part of the bridewealth paid for a young woman, and therefore represent substantial wealth. So do horses, perhaps in even greater measure, as their possession is

Horses are symbolic of wealth all over the world on account of the cost of their upkeep, but in Sumba the symbolism is intensified by the history of Sumbanese horse-breeding, which up until World War II was one of the mainstays of the Sumbanese economy. Sumbanese horses had an excellent reputation with the colonial masters; probably about half of the Dutch cavalry in the Dutch East Indies consisted of Sumba-bred horses. This produced great wealth for the Sumbanese aristocracy, and admiration from the lower classes who depended on them - a combination of power and prestige that ruling classes the world over have found irresistible. On Sumba this has led to a true cult of the horse, and the yearly pasola festival held in West Sumba may draw hundreds of riders. Anthropologist Gregory Forth notes that the inhabitants of Rindi [and presumably those of other regions on Sumba as well] regard the island of Sumba as itself a representation of the horse. Aquatic and amphibian animals such as crayfish, kuru mbia, turtles, tanoma, and of course the above mentioned crocodiles, all stand for noble rank, and one or more associated qualities such as strength, domination, stealth, ferocity, cunning, longevity, or, in the case of amphibians, the ability to mediate between two realms of being. Shrimps, which shed their old shell to reveal the new, symbolize the succession of generations. Other animals frequently depicted are birds, prominent among them the ayam hutan, literally 'jungle chicken', essentially a kind of feral cock, dogs (which in Sumba tend to look far better than elsewhere in the archipelago as they are an appreciated food), deer and lizards. Human figures full of lifeOne of the oldest figurative motifs in Sumbanese ikat textiles is the upright forward facing human figure, nearly always male, that is usually called manusia or manuhia, meaning 'man' or 'mankind'. Similar figures appear in cloth from Borneo and several other Indonesian islands, though in most islands, such as Timor, they have been reduced to geometric abstractions - often to such a degree that to the uninformed eye they are no longer recognizable as human figures. Some experts have speculated that these human figures were introduced into the archipelago with the Vietnamese Dong Son culture, which flourished in the first millennium BC and also introduced bronze artifacts, such as the moko drums of Alor, though apparently not the skill to produce them. Others, noteably Chris Buckley, have refuted the notion that Dong-Son imagery may have influenced Indonesian ikat to a substantial degree.Whatever the true origin of these human figures, the Sumbanese have imbued them with life in a manner that is seen elsewhere only on Borneo, in the pua of Iban Dayak, arguably the only group in Indonesia that surpasses the dying and weaving skills of the Sumbanese. Whether these skills will survive the onslaught of commercial pressures, the commoditization of traditionally meaningful textiles and the concomitant psychological impoverishment of the work involved in producing them, remains an open question. As the Sumbanese have in the past shown a great sensitivity for the demands of the market, we can only hope that worldwide demand for quality, as defined not just by skill, but also by truth to tradition, will outstrip the demand for the quick and cheap. Javanese inspired 'Morning-afternoon' hinggiOne way of pleasing the market was the adoption of so-called pagi-sore patterning. Traditionally, top and bottom of a hinggi were nearly always mirror images of one another. But in pagi-sore ('morning-afternoon') layouts, inspired by high class Javanese batik, one end may be completely different from the other: dragons on top, say, and horses or deer at the bottom. As hinggi are normally made of two identical panels, both of which have tops and bottoms which mirror each other, a weaver would bind skeins of four times the number of threads required for a certain pattern, a tremendously labour saving method. To create pagi-sore hinggi, the number of bindings doubles, as top and bottom are entirely different. (See for instance PC 017.) Pagi-sore hinggi from the early 20th C. are very rare (we have only ever seen one, dating from the 1920s), but they came in vogue, albeit in a minor way, in the 1950. It appears that pagi-sore design was dropped by the late 1970s, or at least used much less, probably because the doubled effort was not rewarded by doubled prices in the market. Some of these cloths pagi-sore cloths from the 1960s and 1970s are quite marvelous and represent some of the best of Sumba ikat work.Borders - plain or elaborate

In the 1970s when some kabakil were made substantially wider, to accommodate figuration. Either plain weft yarn was replaced by ikated yarn, or, more rarely, the motifs were created in warp float weave. Due to their late introduction these elaborate terminals are a useful dating help - with one important caveat: there exists at least one rare example (unlikely to be unique), PC 016 (now in the Kinga Lauren collection), of an early hinggi with ikated kabakil. So perhaps the 1970s appearance of ikated kabakil was not so much an innovation as a revival of a technique that fell into disuse. Definitely an innovation from the same period is an off-white, very finely speckled background - possibly introduced to make cloths look older than they are, but actually very effective as an indication of late manufacture. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||